Originally published in Counterpunch by Michael Colby.

It was twenty years ago last month that Food & Water published our report on Vermont’s atrazine addiction, a toxic herbicide that is banned in Europe but continues to be used in abundance on Vermont’s 92,000 acres of GMO-derived feed corn – all for dairy cows. We used the report to get the attention of Ben & Jerry’s, and it worked. We thought when the doors swung open to the offices of Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield themselves that we’d be able to make the case to them.

It was twenty years ago last month that Food & Water published our report on Vermont’s atrazine addiction, a toxic herbicide that is banned in Europe but continues to be used in abundance on Vermont’s 92,000 acres of GMO-derived feed corn – all for dairy cows. We used the report to get the attention of Ben & Jerry’s, and it worked. We thought when the doors swung open to the offices of Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield themselves that we’d be able to make the case to them.

Our plea at the time was the same as it is today: Ben & Jerry’s should practice what it preaches and help transition its farmers to organic production. If they took the lead, we argued, the entire state could begin a transition away from the kind of industrial, commodity-based dairy system that is wreaking so much havoc with Vermont’s agriculture – and culture. It’s a system that is doing exactly what it was designed to do: chase small farmers off the land by de-valuing production. And so it has been, for decades, an economic death spiral in which less and less is paid for more and more of the commodity product, in this case: milk.

We thought the obvious imbalance – and even direct, outright hypocrisy – between what Ben & Jerry’s was doing and what they were saying would be enough to get these do-good hippies to do the right thing. We were using logic. Because, certainly, the corporation that wanted to “save the planet” and “put the planet before profits” would want to stop being one of the state’s top polluters, right?

Wrong.

We were told at the time, by Ben himself, after a year’s worth of meetings and even an offer of a job to me “to work with us instead of going after us,” that Ben & Jerry’s was not going to transition to organic because it wouldn’t allow them to “maximize profits.” Quick, throw another tie-dyed shirt to the crowd! Or launch a new flavor! Send some ice cream to the schools! Anything, just get the attention off of what Ben & Jerry’s is doing to its homeland, and our homeland – all to maximize its profits.

This was all before they sold out to Unilever, when Cohen and Greenfield still had all the power they needed to do the right thing. But, even then, the harsh reality of profits over ideals was firmly in place, with the belief that if they could convince people that eating ice cream would bring world peace, they could convince them of anything. There was nothing that a little groovy marketing couldn’t fix.

It has, of course, only grown worse under Unilever in terms of corporate accountability and transparency. All the big decisions regarding Ben & Jerry’s are now made from Unilever’s London headquarters, where it also shepherds more than a dozen other billion-dollar-plus brands. But its corporate stand on most everything associated with the gross injustices of its dairy sourcing – from migrant labor exploitation to cow abuse to rural economic plunder – remains exactly the same: stay wedded to cheap, commodity milk, reject an organic transition, and keep relying on marketing to trump the nasty realities. Free cones!

Turns out, those free-cone days that Ben & Jerry’s rolls out every year for Vermonters aren’t so free, nor are the grants they provide to so many environmental and economic justice groups. With each lick and each cash of the foundation check, Ben & Jerry’s expects loyalty to its carefully orchestrated charade: the consumption of high-fat, pesticide-laden, climate-threatening, cow-abusing ice cream produced with the labor of exploited migrant workers all leads to social and ecological justice for all! Come on, people, really?

But let’s keep looking behind the curtain.

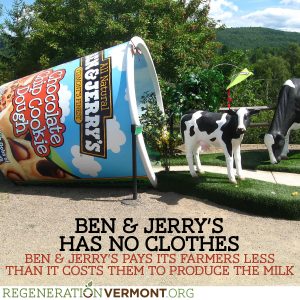

Currently, Ben & Jerry’s pays its farmers less than it costs them to produce the milk. Each load of milk that leaves these farms is, in effect, a donation to the soon-to-be billion-dollar corporation. These farms are losing — on average — upwards of $125,000 a year, piling up debt and holding onto all they know how to do in many cases. At the same time, Ben & Jerry’s annual reports are filled with the optimism of $100 million-a-year growth predictions, Teslas for the executives, and a parent corporation CEO drawing a base salary of $12 million – before the boardroom gifts are doled out.

Just think of this the next time you reach for that pint of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, with dreams of social justice still dancing in your head: On average, for each $5.00ish pint of Ben & Jerry’s, the dairy farmer who produced its foundational ingredient – milk – gets less than fifteen cents from that purchase. And, on average, it costs the farmer about 22 cents to produce that milk. Sadly, the response from Ben & Jerry’s to these facts is to cue the next puppet show, hand out a free cone or two, and sing a song about something else – anything else – but the bitter reality that the unjust and unsafe dairy system it profits from is devastating rural Vermont.

Since Ben & Jerry’s founding in 1978, nearly 3,000 dairy-farm families in Vermont have been forced off the land, with only about 800 remaining today. It’s been a rural recession that never finds bottom, and all exactly as designed, through a cold, calculated devaluation of production. But these weren’t just jobs that were lost, either. It was a way of life, and it was their dignity, too, as generations before them farmed the same piece of land, with no one wanting to be the last. But thousands were.

It is a stark extraction going on, littered with exploitation, and resulting in the kind of environmental destruction that will take generations and billions of dollars to correct. The current bill facing Vermonters for cleaning up our impaired waterways, especially Lake Champlain, the resting place for so many toxins, is approaching $2 billion. State officials estimate conservatively that the pollution from the mega-dairy farms like those supplying Ben & Jerry’s has caused at least half of the damage. Entire sections of Lake Champlain are unswimmable, properties have been devalued, aquatic life is suffering, and drinking water is testing positive for – surprise, surprise — toxins like atrazine and glyphosate (aka: Monsanto’s RoundUp), both used abundantly on Vermont’s dairy-destined cornfields.

Cleaning up the messes from these mega-dairies becomes the public’s problem, with the likes of Ben & Jerry’s and Cabot Cheese taking dairy’s profits while relying on taxpayers to remedy the ecological and social damage in its wake. Consider, for example, the legislative handwringing that went on earlier this year when trying to figure out who and/or what to tax to come up with the down payments for cleaning up the water pollution primarily caused by the mega-dairies. There were all kinds of suggestions – everything from taxing nail salons to property-transfer taxes – but not one proposed source of funds involved having those profiting from the pollution (Ben & Jerry’s and Cabot Cheese, for example) stepping up to pay for the damage.

In practically every other industrial activity in Vermont, from Entergy Nuclear to the PFOA water pollution in Bennington, it is the polluter who is held accountable for their cleanup. Dairy, however, gets a free ride, even though it’s no longer the image-making endeavor it once used to be. The cows have been taken off the hillsides and locked up for what is now a short and sad existence on concrete — far, far from their once majestic grazing selves.

People don’t come to Vermont to see the cows like they used to – it’s too harsh to view now. Sadly, if tourists now think of the cows it’s more to do with how their confinement and concentration has led to runoff that has befouled beaches, made fish uneatable, and decimated the once-quaint villages and towns that thrived under smaller, more diversified agriculture.

It’s not going to be easy but it’s time for a reality check when it comes to Vermont agriculture. We’ve clung for too long to a paradigm that has brought so much economic, cultural and ecological damage – all while the billions in profits get sent elsewhere.

The question for Vermonters is: How much more of this are we willing to take? How many more farms need to go under? How much more water pollution? Cow abuse? Migrant-labor exploitation? Pesticide-contaminated land and food products? How many more billions siphoned off our land and labor?

Ben & Jerry’s has made itself very clear: It’s rather enjoying the record profits. From London, Unilever thanks Vermont for the donation of so much milk and cheap labor, for all the once-bucolic imagery, and for the tax dollars used to cleanup its messes.

For twenty years I’ve been engaging Ben & Jerry’s, showing them the damage that it is doing at every level, from the atrazine report in 1997 to the GMO report in 2016 and a slew of face-to-face meetings in between. But it always ends the same way: Ben & Jerry’s admits that the marketing is working just fine. “People think we’re organic,” is what we were told time and time again in private meetings, while asking them to actually go organic. If fooling people allows for maximizing profits, why stop fooling them?

Ladies and gentlemen, Vermont’s dairy emperor – Ben & Jerry’s – has no clothes.